Last updated on January 30, 2017

Celebrate the small steps?

I teach ancient and medieval history. Gender equality is not a thing in the civilizations my students and I study. Ever. Women are always at a disadvantage – biologically tied to childbirth, socially valuable primarily as wives who bring property or wealth or labor to a family, and economically dependent due to inequitable inheritance laws and educational/occupational limitations.

But that is an exhausting story to tell over and over again. So I spend the semester trying to convince my students to look for ways that women claim agency and societies as a whole take small steps toward greater fairness. In ancient Egypt, women could initiate marriage and divorce. In Han China, Ban Zhao wrote history and pushed for equal education (at least in the aristocracy). In the Roman Empire, gravestones and graffiti women owned property and had a wider variety of careers than many contemporaries. Women hosted church meetings for Roman Christians and missionaries too.

According to the traditional narrative of early Islam, Khadijah convinced Muhammad of his prophetic calling. Women gained new rights to inherit and control their own property (one wonders if Khadijah the merchant had a say in this). In medieval Europe, the abbess Hildegard of Bingen wrote soaring melodies, medical texts, and mystical devotions while she led a community of women dedicated to holiness and simplicity.

In the absence of greater transformation, I say, we must celebrate the small steps.

No. Shatter the ceilings.

My students typically reject my careful narrative in favor of a focus on kickass, exceptional the world over. Their blog posts, this semester and in the past, have focused on:

- Wu Zetian, the first female emperor of China

- Tomyris, the Scythian warlord responsible for the death of Persian king, Cyrus the Great

- St. Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine, often credited with ending the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire

- Matilda, contender for the English throne and mother to Henry II

- Artemisia, a satrap (ruler) under the Persian king, Xerxes, who led her navy in battle against the Greek navy in the Greco-Persian Wars

- Joan of Arc, the medieval mystic and eventual saint

- Cleopatra, ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and one of the wealthiest, most educated persons of her time. (Quite possibly more educated and powerful than Julius Caesar and Marc Antony, thank you very much).

- The Trung Sisters, who led Vietnamese military resistance against China in the first century CE.

I think I know why they choose these women over my midwives, laborers, property owners, and holy women. These women are triumphant, inspiring, and terribly alive. They are #unstoppable, #fierce, #girlpower, #nastywomen in the best possible ways. Heck, I want to cheer when I read the celebration apparent in their posts.

My students, understandably and beautifully, gravitate towards stories that defy oppression and seem to offer hope in the midst of their study of broken social structures and massive inequality. They seek stories of radical, rapid success in the hope that these women’s stories signal progress for everyone.

When it’s not enough.

I had hoped to invite them to cheer with me last week as I announced the election of the first female president of the United States. That wasn’t what happened, of course.

As my colleagues and I watched the results of the presidential election come in, I expressed anger and sadness and frustration at the results. Expressed is the wrong word. I burst out in tears and anger as my hope that we would see our first female president was obliterated. A friend, more gracious than me, offered perspective, “But she ran! On the ticket of a major party. And nearly won. That’s a huge deal. Plus Tammy Duckworth, Kamala Harris, Ilhan Omar…” To which I angrily proclaimed (yelled? I might have yelled…), “That’s not enough!”

I didn’t want small change. I wanted big change. Now. Not just the change that brought with it the election of a female president, but (ideally) the sort of change that ushered into power a president who would listen to the diverse group of people who comprised her electoral base.

We can talk about whether or not those hopes were misplaced some other time. (No really, we can – I’m not trying to put you off forever.) For the moment, I need you just to hear: This was my hope. And it hurt like hell when that hope was crushed.

How do I teach this?

I’m wondering now how best to teach the sort of gender-inclusive history that is so near and dear to my heart in this world that is clearly so desperate for big change, not small celebrations.

How do I present triumphant, resilient, energizing female warriors and rulers – but still communicate to my students the limitations of those exceptional people? Because the historical reality is that these women were awesome, but didn’t always creating lasting change for other female-bodied people. Their reigns or battles didn’t usually create conditions in which other women could achieve the same success. [See Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh; only two women (maybe) officially ruled after her in the next millennium before Ptolemaic rule and all the Cleopatras]. They often perpetuated the worst abuses of their class (which included slavery, conscripted labor, taxation to fund lavish spectacles…pretty standard stuff for the ancient world).

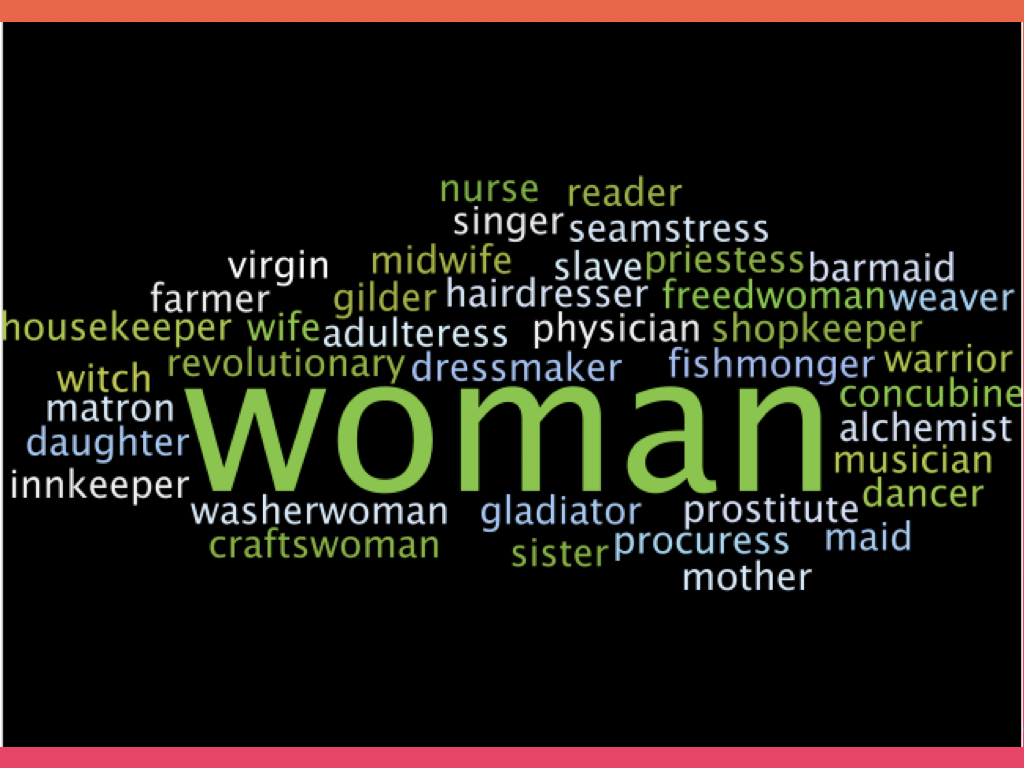

How do I tell them about the inequality that pervades history without leaving them feeling helpless and lifeless? Because the historical reality is that many ‘ordinary’ women lived significant, even remarkable lives. Women’s household labor and craft in China made possible the initial silk production that fueled international trade for the powerful Han dynasty in China. Women have steered new humans into the world on a daily basis in every culture since forever. Women navigated ships in the perilous Mediterranean, they created diplomatic ties between nations through marriage alliances, started new religious movements, and staged anti-war demonstrations.

This is what it takes.

Now that my initial anger has (mostly) passed, I want to find ways to leverage the sort of discontent that makes me and my students desire radical change BUT I also want them to understand that, historically, we have proven ourselves a stiff-necked species, slow to truly disrupt the status quo. I don’t love that about us, but I think it’s true. I wish it wasn’t for the sake of my friends and loved ones who are less safe, more tired, rightfully more frightened than me.

I don’t want to assume how silk makers, midwives, ships captains, demonstrators, political wives, rulers and warriors felt about their work or, in many cases, their minority status in work and the world. I want to give them the respect of not projecting my own agenda onto their lives. But I also want to acknowledge that whether or not they felt like they were working for the betterment of women and of humanity, the lesson of their lives – the thing I want my students to know – is this thing that echoes across the writings of all sorts of workers for justice this week:

It takes difficult, constant, persistent, everyday working, living, and being to create greater freedom of movement, economic freedom, occupational opportunities, and inclusion in religious communities for the populations left out of the best things in society.

It shouldn’t but it does. Also sometimes change happens by accident. And sometimes it doesn’t happen at all. But those are other posts, I think.

I don’t know what this means for my syllabus yet and there are always the limitations of time, institutional expectations, and my own knowledge gaps to deal with. But this is what I’m thinking about. If you’re thinking about that too, leave me a comment or come find me on Twitter. Let’s get to work together.